From Bureaucracy to Bytes and Back

The Evolution of AI in Public Administration

Introduction

This is the first entry in the Governing with AI Living Literature Review. In this entry I trace the evolutionary history of the bureaucracy, with a specific eye towards the bureaucracy’s relationship with automation and digitalization. As you will see, bureaucracies have begun evolving from the classic “street-level” bureaucracy to become “screen-level” bureaucracies — organizations infiltrated by digital computation — and on to “system-level” bureaucracies where algorithms have begun to play a larger role in both government decision making and in government action.

I begin with a brief account of the “ideal bureaucracy” type as described by Max Weber. From here, I trace our evolving understanding of bureaucracies from Herbert Simon’s “administrative behavior” lens, and on to the more recent discussions around digital discretion, artificial discretion, and artificial bureaucrats. Finally, I close with some reflections on what this literature suggests for the future of bureaucracies in a world where advanced AI continues to proliferate throughout the governance ecosystem.

From Bureaucracy

To govern, to steer, to control, one must have an administrative apparatus, something that administers power. Pharaohs, Emperors, Kings and Queens understood this. And now, Presidents, Prime Ministers, and yes, Kings and Queens still understand this. Throughout history, and until present day, it has been bureaucracies, wielded by governments to conduct public administration (and war), that have shaped the countless lives of the people living under the rule of those governments.

For many, “BUREAUCRACY” is a dirty word. And, fair enough! Bureaucracies have done, and continue to do, some dirty things. They even sometimes spread ADMINISTRATIVE EVIL. But this is just one side of the coin that is bureaucracy. Just as with markets, bureaucracies do bring about harm, but, as with markets, bureaucracies are necessary for modern life, and so many of the social and physical goods that are found across the globe. The bureaucracy is one serious piece of the backbone of both modern and historical civilization.

While the basic concept of a bureaucracy has been practiced at least as long as we’ve had writing, record keeping, and governments, it was not considered a formal object of modern study until Max Weber’s Economy and Society was first published in 1921. Weber had this notion of “ideal type” which he applied to describing the structure of bureaucracy. For Weber, the ideal type of bureaucracy included:

Well-defined and organized competencies.

A hierarchical organizational structure, with codified channels for making and

transmitting information and decisions.

Modern administration that is based on:

documents preserved as original copies or concepts, and

a bureau that includes a staff of subordinated bureaucrats and writers of all kinds, working in the office, together with relevant resources including material goods and documents.

The work of the bureaucrat usually requires significant training for the specific tasks to be accomplished.

A full-fledged position occupies all the professional energy of the bureaucrat to process its tasks, regardless of limits to his mandatory working hours.

The duties of the position undertaken by the bureaucrat are based on general learnable rules and regulations, which are more or less firm and more or less comprehensible. The knowledge of these rules and regulations thus constitutes a special kind of ‘applied science,’ which the bureaucrat possesses.

While Weber had a particular view of bureaucracy, it was Herbert Simon (1947;1997) who offered an account of bureaucracy through the lens of information processing rather than describing the desired ideal bureaucratic structure that Weber offered.

For anyone who knows a little bit about the rest of Simon’s career, it should not be surprising that this was his take. Simon also pioneered the field of AI, which, at its core, is intimately concerned with information processing. Later in his career, in the final edition of his classic work “Administrative Behavior” (1997), Simon even more directly tied the rise of computational power (as a source of information processing) to the workings of administrative behavior of administrative organizations.

Enter the Bytes.

Simon noted that, even in 1997, digital computation had already begun to play a major role in how organizations processed information. Simon astutely noted that we were moving from a world where information itself was the bottleneck to high-quality organizational decision making to one where the attention of administrators themselves would become the bottleneck. The trick, it turned out, was still to identify the relevant information that needed to be applied to a particular decision. This was the beginning of a deep encroachment of bytes into bureaucracy.

A mere 5 years later, bureaucracy scholars Bovens & Zouridis, laid out, in detail, what they saw as digital computation’s increasing presence within public administration and what this signaled for the evolving shape of bureaucracies themselves. Bovens & Zouridis (2002) argued that bureaucracies were on an evolutionary pathway from “street-level” bureaucracies (those that might resemble Weber’s classic conceptualization) on to “screen-level” bureaucracies, and were rocketing towards a new form of bureaucracy called “system-level” bureaucracy. Screen-level bureaucracies described an evolutionary type where human bureaucrats began to see much of their work mediated through the interface screen of their personal computer monitors. These authors observed that much administrative work was beginning to be completed while staring at these monitors and entering digital data into a variety of digital databases.

However, Bovens & Zouridis could see that these screen-level bureaucracies were not the final evolutionary type. A simple extrapolation of the trend in utility and usage of both digital computation and algorithmic, automated analysis would show that these tools were likely to increase their presence within bureaucracies. They called the next evolutionary type of bureaucracy the “system-level” bureaucracy. In these bureaucracies, the role of automation, computation, and AI would further supplant the role of the individual discretion of the human bureaucrat. That is, while screens had augmented the capabilities of individual bureaucrats, in a system-level bureaucracy AI would automate much of the decision-making process, the information processing, within bureaucracies. Human discretion would be replaced by digital discretion for completing countless organizational tasks, and from our vantage point in 2024, we can see this was quite prescient.

But what does the proliferation of digital discretion mean for public administration?

This has been an area of inquiry within public administration for the last decade or so. The most well known piece on the topic is Busch and Henriksen’s (2018) “Digital Discretion: : A systematic literature review of ICT and street-level discretion” In this piece, Busch and Henriksen survey the evidence and the commentary on how digital computation (see: information and communication technology of ICT) had begun restructuring the way in which decisions were being made within bureaucracies. In their conclusion, Busch and Henriksen state:

In this study, we report from 44 scholarly articles on ICT and street-level discretion. Societal problems such as increasing and more complex demands on public service provision, and errors and corruption are creating pressures on politicians and government officials to provide services of higher quality and in a more efficient manner. The review shows that the environment in which ICT is implemented and used is vital for understanding why digital discretion diffuses and how the impacts of it are. For certain types of street-level work such as mass transactional tasks, ICT has reduced or even eliminated the use of human judgment. Examples of mass transactional tasks are the handling of student grant loans and tax reports where the data is numerical and readily available for government agencies, and where decisions are made based on schematic rule sets. In other types of street-level work such as social work, the discretionary practices of street-level bureaucrats are influenced by ICT to a lesser degree or not influenced at all. Contextual explanations for the prevalence of digital discretion can be attributed to factors such as the degree of professionalization, formulation of rules, computer literacy, and the level of information richness required. The impact of digital discretion is less explored in types of street-level work in between these extremes which opens avenues for future research. Another promising area for future research seems to be the increasing use of advanced technology such as artificial intelligence. This technology is now to a considerable extent able to deal with tasks of high complexity, and can thus address many of the shortcomings that the critics of digital discretion put forward…….

We conclude the literature review with claiming that the scope of street-level bureaucracy is decreasing. While certain types of street-level work seem to avoid extensive changes due ICT, it makes more and more sense to talk about digital bureaucracy and digital discretion since an increasing number of street-level bureaucracies are characterized by digital bureaucrats who operate computers instead of interacting face-to-face with their clients.

Busch and Henriksen were observing a change in the literature. Human discretion was beginning to be replaced by digital discretion. For more “standardized” tasks, those identified as “mass transactional tasks” by these authors, digital discretion was beginning to replace human discretion. However, for more complex tasks, less routine tasks, tasks where professional norms and judgements are needed digital discretion still fell short of human discretion. However, Busch and Henriksen, even in 2018, saw that AI may eventually be able to handle these more complex cases and overcome the limitations of digital discretion.

One additional study from 2018 points at a particular case study worth briefly exploring, Hansen, Lundberg, and Syltevik’s “Digitalization, street‐level bureaucracy and welfare users' experiences.” They explore the case of NAV:

Our case concerns the Norwegian Welfare and Labour Organization (NAV). In addition to the need to seek a more empirically grounded understanding of ICT in welfare bureaucracies, we focus on NAV for three reasons. First, NAV is one of several welfare bureaucracies around the world that has implemented ICT on a broad basis. The NAV organization is at the forefront of these developments, and it faces the same problems as the others. Second, as is the case for welfare agencies in other Scandinavian states, NAV is a large and important part of Norwegian society. Approximately one-third of the Norwegian state budget is spent by NAV on services and benefits provided to citizens. In any given year, NAV serves half of the Norwegian population and manages over three million cases. Some receive benefits on the basis of easily verifiable criteria without face-to-face interaction, whereas others struggle with problems that require frequent interaction with NAV over a longer time. How individuals manage their situation and their experiences may vary depending on factors such as their education, age, language and other skills. Thus, NAV is an excellent site for exploring both the limitations and possibilities of new technology for service users. Third, NAV is an interesting case because the Norwegian population is at the forefront, worldwide, of the use of new web technology. Sixty-seven per cent of the population are daily users of Facebook (TNS Gallup 2013), 97 per cent have internet access, and 80 per cent use the web daily (Vaage 2013). Thus, when NAV adopts new technological devices, it does so under what could be described as the best possible circumstances.

In this case, while exploring the evolutionary case of NAV from ~2008-2016, the authors found that the transformation to screen- and system-level bureaucracies had not (yet) taken place at NAV.

The effect on the relationship between users and the organization is complex. Bovens and Zouridis’ (2002) vision of screen- and system-level bureaucracy has not been a characteristic of the development of NAV so far. This is consistent with research in other countries, which shows only marginal shifts towards system-level bureaucracy (cf. Buffat 2015; Reddick 2005). NAV is a street-level bureaucracy that has some features of a screen-level bureaucracy for some groups. Currently, new technology has not replaced face-to-face encounters. This may be explained by the recentness of these ICT developments and the difficulty of developing well-functioning ICT systems, and because NAV still offers other contact channels. If this is altered, the effect of the emerging digital divide on access to welfare services and benefits could be strengthened. Until now, what we have seen for users with more complex dealings with NAV is more of a hybrid nature, combining digital and traditional communication. In some users’ dealings with NAV, ICT may reduce face-to-face contact, while for other users there is supposed to be more face-to-face contact. One example of this is the process of making individual activity plans that require personal contact. Such plans are an important tool in activation programmes in Norway.

The NAV case highlights that even under somewhat ideal circumstances (population at the forefront of technological adoption), NAV had not evolved into a full screen- or system-level bureaucracy. That, instead it was better still thought of as a street-level bureaucracy that had begun combining both digital and traditional (face-to-face) communication.

Additionally, In 2022, Henriksen coauthoring with a different colleague, Ranerup offers another case study to explore in the paper titled “Digital discretion: Unpacking human and technological agency in automated decision making in Sweden’s social services”. In this article Ranerup and Henriksen describe the case of the Trelleborg Model.

Trelleborg, the first municipality in Sweden to use automated decision making for social assistance decisions. This innovation project, the Trelleborg Model, is a management model now used in many other municipalities in Sweden. Trelleborg, Sweden’s southernmost town, is an industrial town of around 45,000 people.

Below is Figure 1 taken directly from Ranerup & Henriksen’s (2022) “Digital discretion: Unpacking human and technological agency in automated decision making in Sweden’s social services.” This Figure 1, from their article, highlights the way in which the citizen interacts both with caseworkers (human discretion) and a digital application and algorithmic decision (digital discretion). Here we also see something of a hybrid approach where human and digital discretion are applied at different places in the decision making process.

In this hybrid process described above, the authors find that the elements of digital discretion plausibly lead to improvements in the achievement of ethical values, democratic values, and professional values. However, the limitation here is that digital discretion is only being applied to standardized, and routine decisions. Despite this the article finds that the Trelleborg Model still provides for improvements on : 1) avoiding unethical actions and corruption, 2) adherence to rules and procedures that can be codified, 3) empowering citizens by giving them a more active role in decisions affecting their lives and rights, 4) increasing governments’ political legitimacy, 5) increasing decision-making accountability, 6) improvements in the quality of decisions, 7) increased efficiency, 8) preventing errors, and 9) reducing the cost of case management.

Taken together, this suggests that while digital discretion has not transformed Trelleborg’s approach to welfare service delivery, the deployment of digital discretion has provided many improvements to service delivery. The organizations covered in these cases had not been radically transformed by the introduction of digital discretion, but, while human discretion may be waning for some task sets, digital discretion remained restricted to making improvements on tasks where little discretion is required and the decisions to be made are routine and standardized, as is often the case with social insurance benefit programs.

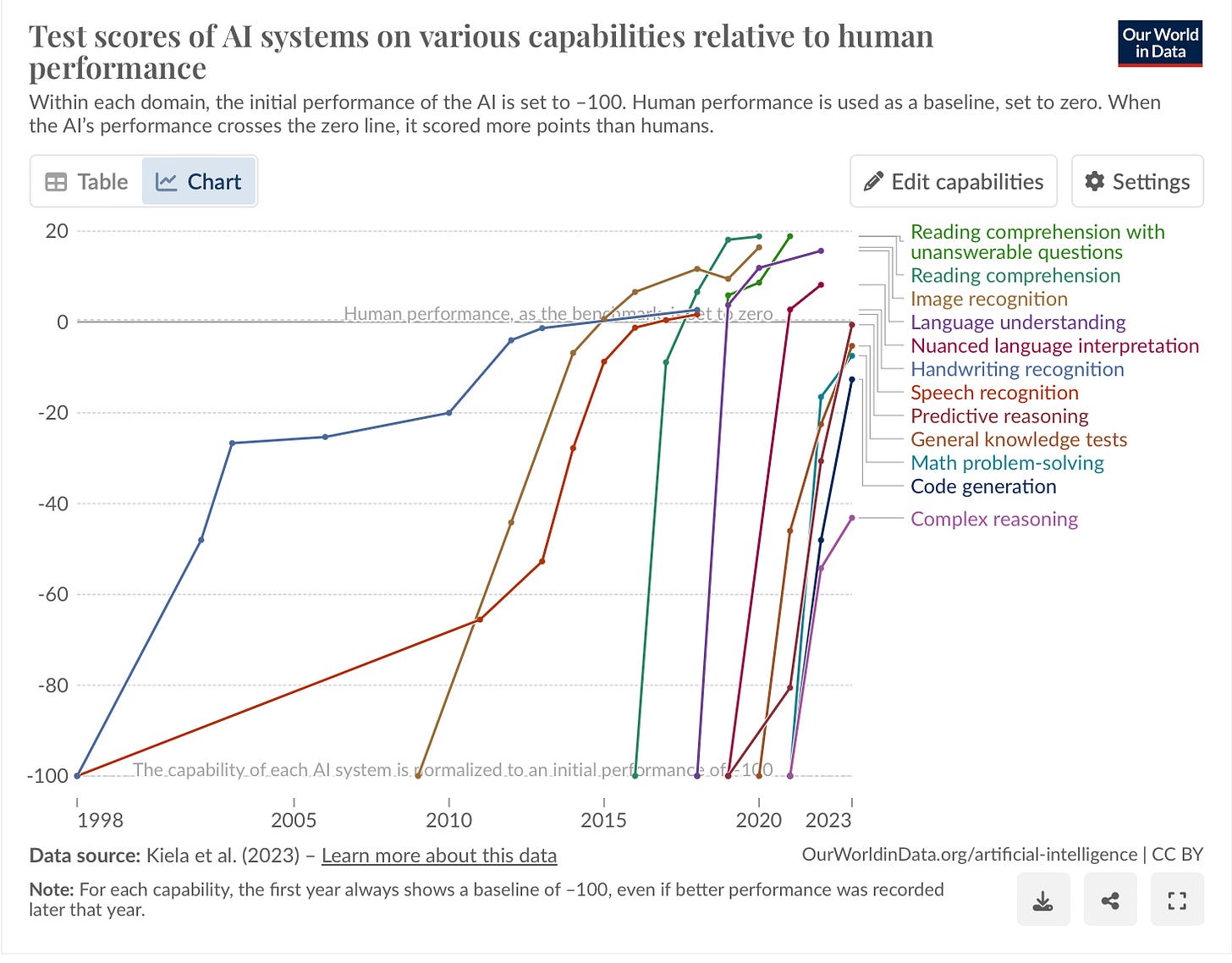

With digital discretion being deployed, technological advancement carries on. AI, in particular, has seen a dramatic leap in capabilities. As AI systems did begin to show capability improvements, they began to receive more attention in the literature.

The Rise of Artificial Discretion and Artificial Bureaucrats

Concurrent with the discussion on digital discretion, there also developed a line of inquiry into artificial discretion. While digital discretion is a slightly more broad concept, artificial discretion explores how AI in particular is deployed to make decisions and pursue actions within the bureaucracy. This concept was introduced into the literature in 2019 in a paper titled “Artificial discretion as a tool of governance: a framework for understanding the impact of artificial intelligence on public administration.” In this paper, Young, Bullock, and Lecy extensively argue that while AI may be applied to a wide array of tasks within governments, there are a number of important issues within public administration that bureaucrats need to consider before widely deploying these tools.

In this article, the authors identify their different uses of AI based upon the level of discretion required for completing that task. The authors argue that for tasks that require low discretion, complete automation may be the most appropriate use of AI. For medium discretion tasks, AI can be used as a decision-support tool and for predictive analytics. Finally for tasks that require high discretion, AI can be used for new data generation, reduction of data complexity, and relationship discovery. Table 1 from this paper, which summarizes this relationship between AI use and discretion required, is provided below.

In addition to this general relationship between the use of AI and discretion required, the authors also examined the use of AI at different levels of organizational analysis. These levels are the micro-level (individual decisions), meso-level (organizational decisions), and the macro-level (institutional decisions). The authors give examples of each of these tasks in the Table 2 from their article, which is included below.

The following year two of these colleagues Young and Bullock with another colleague Wang explored two cases of how AI was reshaping not only how individual decisions were made but also the evolution of bureaucracies as well. In “Artificial intelligence, Bureaucratic Form, and Discretion in Public Service” (2020) these colleagues looked at the two cases of policing and insurance processing. Their argument is that different policy domains contain different bundles of tasks that require relatively more or relatively less discretion. In this case policing is designated as often requiring medium to high levels of discretion while insurance processing tasks generally require lower levels of discretion. The authors go on to use this reasoning to explore changes in both the ratio of human to artificial discretion and the magnitude of change in the bureaucratic form. The findings are summarized in the authors’ Table 2, which is included below.

Back to Bureaucracy

As this entry in the living literature review has highlighted, what has traditionally been considered as AI is already at work within and throughout bureaucracies, placing evolutionary pressures upon them. But several key considerations are still missing from the current story of governing with AI. For example, currently, we are in the midst of a gigantic leap in the capabilities and generality of AI systems. The progress over the past 10 years has been well documented. This progress was punctuated on November, 30th of 2022 with the release of ChatGPT.

The question is: what does this mean for bureaucracies? What does it mean for “governing with AI”?

This will be a consistent focus for following entries in this living literature review.

So, when we turn “back to bureaucracy” itself, in large part what we’re considering here is, in an age of rapidly improving AI capabilities, how will the government administrative apparatus itself administer power?

Will bureaucracies remain as the relevant organizational type?

Conclusion

This first entry in the Governing with AI Living Literature Review has explored the evolution of AI within Public Administration. An understanding of this history is needed to understand how frontier AI systems will result in a further evolution of bureaucracies and public administration.

Bureaucracies have a long history in administering government power. Max Weber described the “ideal type” bureaucracy in 1921. In 1947, Herbert Simon added to this description by putting a focus on information processing by bureaucracies. By 1997, Simon saw how digital computation was beginning to infiltrate the bureaucracy. By 2002, Mark Bovens and Stavros Zouridis had begun to see a deep evolution of bureaucracies from the classic street-level bureaucracies on to screen-level and system-level bureaucracies. In 2018, Peter Busch and Helle Henriksen observed that as part of this evolution, human discretion was being replaced and augmented by digital discretion. By 2019, Matthew Young, Justin Bullock, and Jesse Lecy were exploring under what circumstances artificial discretion should be used by bureaucracies.

But, in 2022, ChatGPT was released and generative pre-trained transformer AI models burst onto the public scene. These “foundation models” heralded a new age of AI, characterized by increasing intelligence and generality. And while this entry in the living literature review has set the historical stage for the entrance of these frontier AI systems, the next several entries will explore the direct impact of these systems on how governments administer power.

References

Bovens, M., & Zouridis, S. (2002). From Street‐Level to System‐Level Bureaucracies: How Information and Communication Technology is Transforming Administrative Discretion and Constitutional Control. Public Administration Review, 62(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00168

Buffat, A. (2015). Street-Level Bureaucracy and E-Government. Public Management Review, 17(1), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.771699

Bullock, J., Young, M. M., & Wang, Y.-F. (2020). Artificial intelligence, bureaucratic form, and discretion in public service. Information Polity, 25(4), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-200223

Busch, P. A., & Henriksen, H. Z. (2018). Digital discretion: A systematic literature review of ICT and street-level discretion. Information Polity, 23(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-170050

Hansen, H., Lundberg, K., & Syltevik, L. J. (2018). Digitalization, Street‐Level Bureaucracy and Welfare Users’ Experiences. Social Policy & Administration, 52(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12283

Ranerup, A., & Henriksen, H. Z. (2022). Digital Discretion: Unpacking Human and Technological Agency in Automated Decision Making in Sweden’s Social Services. Social Science Computer Review, 40(2), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320980434

Reddick, C. G. (2005). Citizen interaction with e-government: From the streets to servers? Government Information Quarterly, 22(1), 38–57.

Simon, H. A. (1997). Administrative Behavior (3rd ed.). Free Press.

Simon, H. A. (1947). Administrative Behavior (1st ed.). Macmillan.

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (Vol. 1). Univ of California Press.

Young, M. M., Bullock, J. B., & Lecy, J. D. (2019). Artificial Discretion as a Tool of Governance: A Framework for Understanding the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Public Administration. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, gvz014. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz014